Many people struggle to control their use of digital devices: With news updates, engaging games, and an endless stream of social media available at your fingertips, it is difficult to avoid being distracted or sucked in.

In fact, having good self-control over your device use is often made difficult on purpose, because the business models of many tech companies depend on people using products and services as much as possible. Think of psychological tricks like clickbait articles, infinitely scrolling newsfeeds, and the semi-random ping of bright red notifications, designed to lure you in.

But what might design look like that tries to do the opposite: Help (rather than prevent) people exercise self-control over their device use?

On the online stores for apps and browser extensions, there’s now a large market for ‘digital self-control’ tools that do exactly this. They come in many forms—from browser extensions that lock you out from social media or hide Facebook’s newsfeed, to apps that gamify self-control by giving you points or badges for using your device as intended. Some of them—like Forest, which cuts down a virtual tree if you use your smartphone while in focus mode—have millions of users.

This is not an entirely new development—Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) researchers have developed similar tools for a few years—but it is gathering momentum as Apple and Google recently reacted to these trends by building features for self-tracking and self-limiting into their mobile operating systems.

Many tools help support self-control over device use, using tricks such as blocking access to distracting websites (top left) or cutting down virtual trees if you use your smartphone during a focus session. Apple (bottom left) and Google (bottom right) recently begun to build similar functionality into their mobile operating systems.

Yet little is known about how these tools work. What novel features do they use to encourage digital self-control? What does psychology say about how they might work?

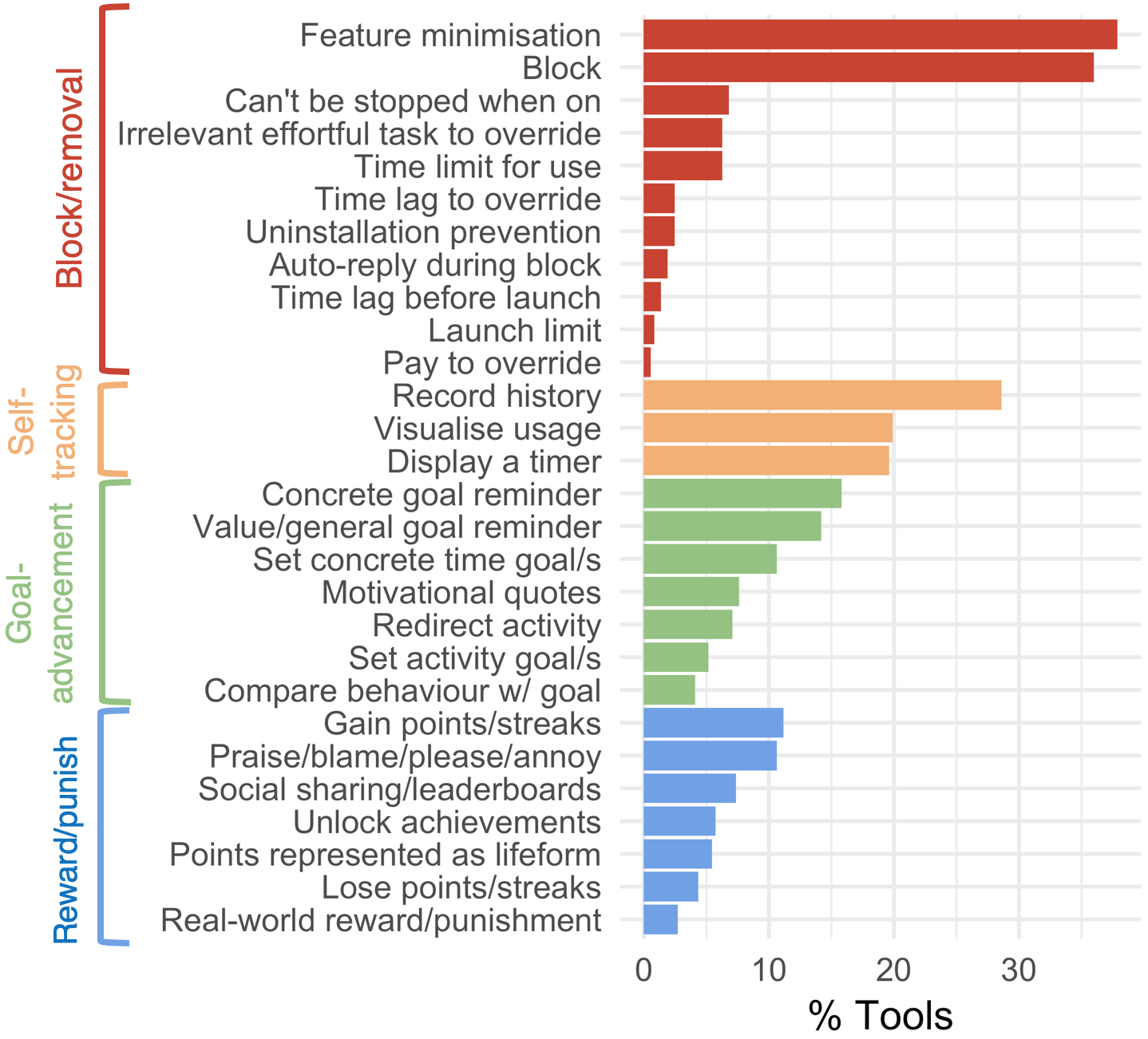

To address this gap, we analysed design features in 367 apps and browser extensions for digital self-control on the Google Play, Chrome Web, and Apple App stores, and used a ‘dual systems’ model drawn from cognitive neuroscience to organise their interventions and explain why they might work.

Our work helps guide future research by pointing to i) widely used or theoretically promising features of current tools that are underexplored in HCI, ii) rarely targeted psychological mechanisms that could be promising ground for new tools.

What do current tools do?

You can see all the tools we analysed in this Google sheet. This plot shows the overall percentages of tools that included common features:

Block or remove distractions (74% of tools)

The most common type of feature is to block or remove distractions. That is, a tool might enable people to block themselves from using specific apps or websites or their smartphones altogether, or, it might remove specific distracting features within the services they use.

For example, the Chrome extension Focusly allows people to block their own access to websites on a blacklist. In addition, it helps people stick with their intention by requiring them to type in a series of 46 arrow keys in a specific order, before they can stop a blocking session.

blocks access to websites on a blacklist, then helps people stick with their intention by requiring them to type in a series of 46 arrow keys in a specific order, before they can stop a blocking session.](/post/2019-04-30_367-tools-of-resistance/4effort_small.jpg)

Focusly blocks access to websites on a blacklist, then helps people stick with their intention by requiring them to type in a series of 46 arrow keys in a specific order, before they can stop a blocking session.

The perhaps most popular example of removing distracting functionality is the Chrome extension News Feed Eradicator, which removes the newsfeed from Facebook and replaces it with a motivational quote. Many similar extensions do things such as remove suggested videos on YouTube, and some Android apps limit the amount of functionality available on a smartphone’s home screen.

removes the newsfeed from Facebook and replaces it with a motivational quote](/post/2019-04-30_367-tools-of-resistance/5eradicator.jpeg)

News Feed Eradicator removes the newsfeed from Facebook and replaces it with a motivational quote

Self-tracking (38% of tools)

Many other tools record and visualise how people use their device, or display timers so that people can keep track of how long they’ve stayed on task.

For example, RescueTime tracks how people use their laptops and displays visualisations of how that time was spent. A good number of these tools focus on how long people manage not to use your phone, such as the iOS app Checkout of Your Phone.

(left) tracks and visualises time spent on laptops. [Checkout of Your Phone](https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/checkout-of-your-phone/id1051880452?mt=8&ign-mpt=uo%3D4) (right) tracks how long you’ve time you’ve managed not to use your smartphone.](/post/2019-04-30_367-tools-of-resistance/6rescue.png)

RescueTime (left) tracks and visualises time spent on laptops. Checkout of Your Phone (right) tracks how long you’ve time you’ve managed not to use your smartphone.

Goal advancement (35% of tools)

Another common approach is to include features for nudging people towards working on the right tasks when they actually use their devices. For example, the Chrome extension Todobook replaces Facebook’s newsfeed with a todo-list which reminds the user of their tasks. Another example is the iOS app Time, a todo-list with a countdown timer that provides continual task reminders if the user leaves the app.

Reward or punish (22% of tools)

Finally, many tools include features that reward or punish people for how they use their devices. A well-known example is Forest, which grows virtual trees that may be killed if one’s device is used inappropriately. Numerous clones exist of this idea exists, where other virtual creatures (e.g. a goat, fish, donuts) are harmed or lost.

Other tools add real-world rewards or punishments, for example by making people pay money out of their bank account if they spend more than 1 hour on Facebook in a day (Timewaste Timer). The most extreme example is PAVLOK which lets the user automatically administer themselves actual electrical shocks via a bracelet when they try to access websites on a blacklist (!).

takes money out of your bank account if you spend too much time on Facebook; [PAVLOK](https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/pavlok-productivity/hefieeppocndiofffcfpkbfnjcooacib?hl=gb) lets you automatically administer yourself electrical shocks via a bracelet if you try to access blacklisted websites.](/post/2019-04-30_367-tools-of-resistance/8reward.png)

(Timewaste Timer takes money out of your bank account if you spend too much time on Facebook; PAVLOK lets you automatically administer yourself electrical shocks via a bracelet if you try to access blacklisted websites.

The Psychology Behind the Tools

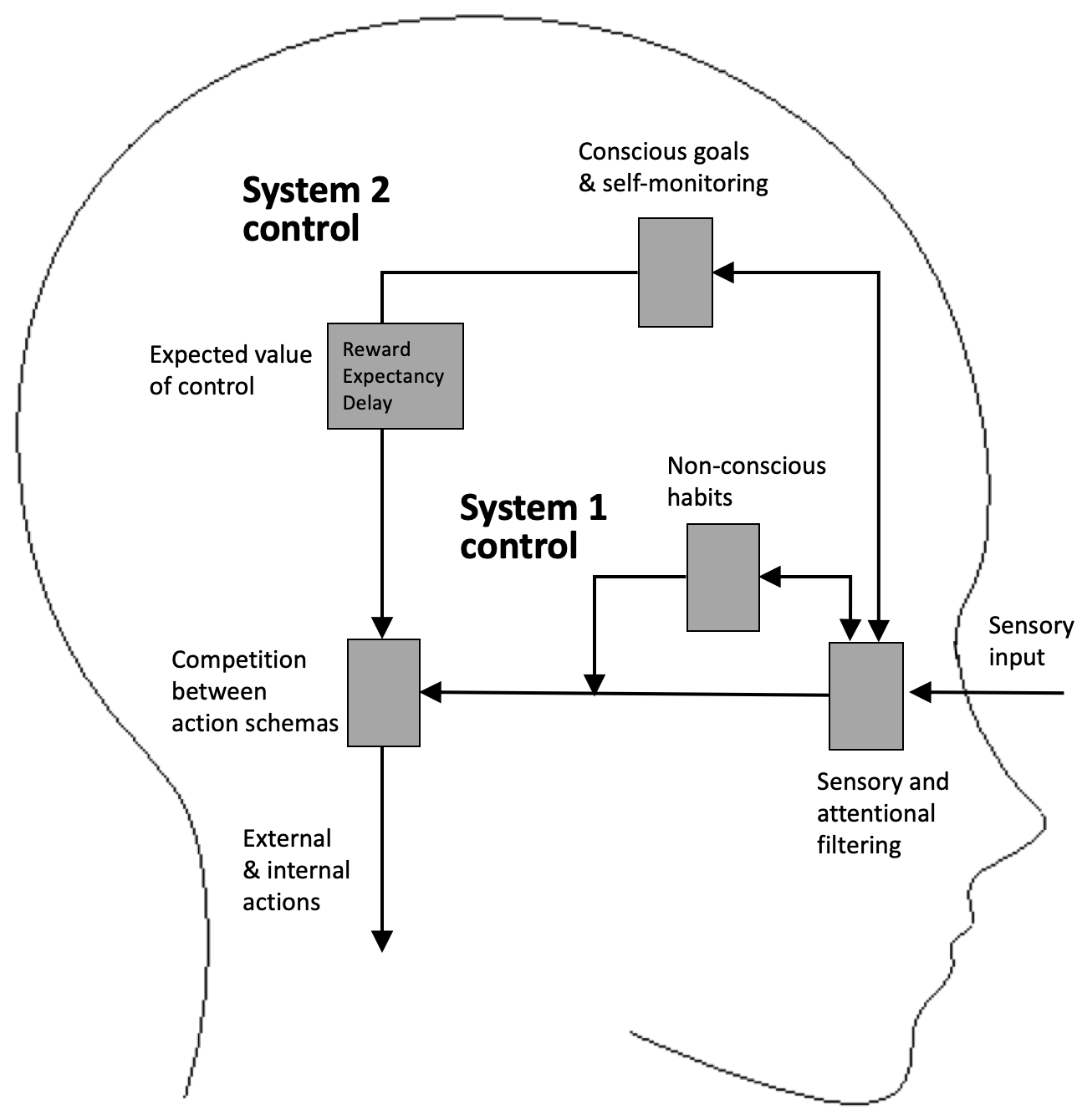

A useful way to think about the psychological mechanisms targeted by all these tools is in terms of a ‘dual systems’ model. Simply put, such a model separates our behaviour control into two types: automatic, non-conscious control (‘System 1’), and deliberate, conscious control (‘System 2’):

System 1 control is when our behaviour results from habits or instinctive responses that get triggered by external stimuli and internal states, with no need for conscious attention. For example, if you find yourself pick up your smartphone to check for notifications out of habit.

System 2 control is when our behaviour is triggered by goals, intentions, and rules held in conscious working memory. For example, if you have a goal to text a friend using Facebook Messenger and take out your phone to do so.

Self-control is to use our conscious System 2 to override automatic System 1 responses when the two are in conflict. For example, you might have a goal to not check your smartphone for notifications at a dinner and need to suppress your habit of doing so.

Sometimes we fail at self-control, even when we’re aware of if in the moment. Neuroscientists think this comes down to the expected value of control, which is a cost-benefit analysis of what you might gain from exerting self-control. The three main elements of this are:

- the amount of reward you could obtain (or loss you may avoid)

- how likely you think it is that you will be successful in exerting self-control (expectancy)

- the delay before you get the potential reward.

A summary of the dual systems model of self-regulation. System 1 control refers to habits or instinctive responses that get triggered by external stimuli or internal states. System 2 control refers to behaviour triggered by consciously held goals or intentions. Self-control is to use conscious System 2 control to override System 1 responses when the two are in control. The strength of conscious self-control depends on the expected value of control, a cost-benefit analysis of what you might gain from exercising self-control.

This model is one powerful way to think about the features of digital self-control tools in terms of the psychological mechanisms they target. For example:

- goal advancement tools help self-control by making sure the user is consciously aware of their goals, so that they are able to attempt to exert System 2 self-control in the first place

- reward/punishment tools help self-control by influencing the expected value of control; tools like Forest provide an extra reward that makes System 2 self-control more likely to succeed

- block/removal tools take a more crude approach and helps self-control by simply removing content that would trigger unwanted automatic habits or risk crowding out conscious goals from working memory

Research pointers from the current landscape of self-control tools

Many specific approaches stand out from our tool review as obvious candidates for research, because they have been underexplored, including:

- Responsibility for a virtual creature: As mentioned, Forest is the most popular tool to take this approach (with over 5 million users on Android alone), but this use of virtual pets for digital self-control haven’t been evaluated yet by any research.

- Redirection of activity: Timewarp automatically reroutes the user to a website aligned with their productivity goals when they navigate to a ‘distracting’ site (e.g. from Reddit to Trello). Lots of tools implement similar functionality, and it resonates well with suggestions by behaviour change researchers, but it haven’t been evaluated.

Looking at the market through the lens of psychological mechanisms targeted, we also identify avenues for novel design efforts:

- Delay: Only 4% of the tools we reviewed focused directly on using time lags to help self-control. This should be somewhat surprising to researchers because time lags—especially online—have strong effects on our behaviour.

- Expectancy: Few tools directly targeted the user’s perception that she will be able to succeed in exerting self-control. This component is central to many theories of self-regulation (e.g. Social Cognitive Theory), so may also be an important to target in future tools.

The landscape of current tools amounts to hundreds of natural experiments in supporting self-control over digital device use, and there are many more lessons to draw from its current state. In this blog post, we can only pick up the main points—go read the actual paper for more!

(left) replaces Facebook’s newsfeed with a todo-list; the iOS app [Time](https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/time-defeat-distraction/id1313017655?mt=8&ign-mpt=uo%3D4) (right) is a todo-list which provides continual task reminders if the user leaves the app.](/post/2019-04-30_367-tools-of-resistance/7todo.png)

Comments

I use the open source, zero-tracking utteranc.es widget for comments - it's built on GitHub issues, so you need a GitHub account to comment.